by Reed Dyer

As educators dedicated to school improvement, we need to start apologizing more often. That’s because the work of school improvement is messy and pushes us all into the area where mistakes and missteps are inevitable. True school improvement is about fighting for equitable outcomes for all students and that involves talking about identity and beliefs. Conversations about identity and belief systems are at the heart of true change, but can also be a minefield of mistakes.

We make a comment about parents and realize we’re stereotyping the families on that side of town.

We express frustrations about a student’s behavior that reveals a hidden bias toward boys of color.

We question a colleague’s approach to assessment and it comes across as an attack on their professionalism.

Still, we can’t hold ourselves to the highest expectations without pushing ourselves beyond what we already know how to do well or right. In doing so, we’re going to make mistakes. We may even do things intentionally that we later realize were off the mark. But we can’t let that stop us; we can and must make mistakes while still being civil, good people. When we mess up, we need to move forward. To move forward, we need to apologize.

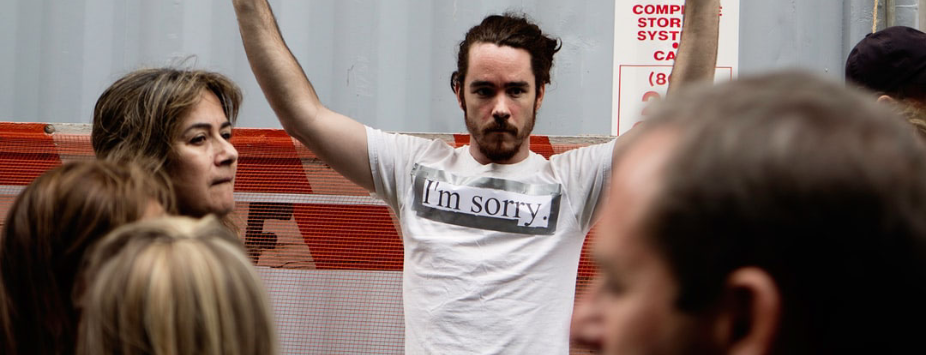

Step one: Say, “I’m sorry.”

This may seem obvious, but it’s sometimes overlooked. We sometimes tell kids that you shouldn’t say sorry if you don’t feel sorry. I call bunk on that. Regardless of how you feel, if you owe someone an apology, you should say, “I’m sorry.” Of course, it’s best to mean it. To feel it. But that can sometimes be hard, especially when you didn’t intend to offend or hurt someone. Your intention is not the point; it doesn’t excuse your impact. For that reason, always apologize. Saying, “I’m sorry,” is a starting point. A way back to common ground.

Step two: Name it, and pledge not to do it again.

Whatever you did wrong, name it, own up to it, and make a clear commitment not to do it again. Can you actually guarantee that you’ll never make the same mistake? Probably not. But you can promise to make every effort. This step is important in two ways. First, it shows that you recognize the specific error you made. Being clear that you can pinpoint the misstep—and its impact—shows the impacted party that you understand their point of view. Naming your mistake and pledging not to repeat it also signifies that you are willing to take responsibility for the impact of your behavior moving forward, even if your intentions were good all along.

Step three: Ask what else you have to do to make it right.

Hopefully by now we’ve accepted the idea that impact is more important than intent. To make progress in schools, we have to move past saying things like, “I’m really sorry if you felt offended.” We have to reach a point where we understand and accept that we did the offending.

After apologizing, it’s important to ask your colleague or colleagues what you can do to move toward forgiveness. Then, listen. Really listen. What can you learn from them? What do they need from you? This is the hardest step. You’re not in control here and it may not be easy for your colleague or colleagues to voice what they need. In fact, depending upon the power dynamics at play—including role, race, gender, age, and other aspects of identify—your colleague or colleagues may not be ready or able to voice what they need.

Still, offering to listen gets to the heart of an apology. You have to relinquish control. You have to ask: What do you need? You don’t know and that’s the point. Hand over the power and start listening.

The power of words

When you make a mistake, say you’re sorry. Promise not to do it again, and do your best to keep that promise. Ask how else you can make it better. It’s striking how often we expect such behavior from children and how little of it we do as adults. When my son makes a mistake, I want him to verbally apologize, show remorse, and generally fall on the sword for his missteps. And he’s ten. Yet, I often expect less of myself—and my colleagues.

In too many schools, we have built and fostered a culture of “nice,” and in doing so fail to push ourselves and our colleagues outside of our comfort zones. This only reinforces the status quo that leaves many students, predictably, behind. We know we need to change how we talk, what we prioritize, and who we fight for. But that inevitably leads to mistakes, hurt feelings, and misunderstandings. So what? When we apologize, those mistakes stop resulting in barriers and start resulting in progress.